She told me she remembered Black Sunday, that she’d never forget it in fact, because she was just a little girl, and her family was in church. It was a Sabbath afternoon. It was Palm Sunday too, the first day of Holy Week, and her family was at worship when “the roller” came in, a curtain of darkness, a huge wall of dust swept up from ground shorn of its ancient grasses. When that roller arrived, she said, the church filled with dust, blinding them all. What she had never forgotten was that the only thing she could see up front behind the pulpit was the pastor’s white collar.

It was April 14, 1935, and all over South Dakota, a “black blizzard” swarmed into churches and barns and houses, through villages and towns. No one escaped. It wasn’t the first and wouldn’t be the last, but it was the biggest, something none who were there could ever forget.

A woman from Springfield who remembered that Sunday told me she had laid out her children’s everyday clothes on their beds upstairs before the family left for church that morning. When they returned returned, “Black Sunday” had deposited so much dust over everything inside their farmhouse that the outlines of those clothes on the beds upstairs simply weren’t discernable at all. The house was that full of dust.

Frederick Manfred’s very first novel, The Golden Bowl, is the story of a man named Maury, who is looking frantically for work, mid-Depression. His parents are already gone, destroyed by the dust in Oklahoma. He’s come to South Dakota because he’s heard there’s work in the mines out west in the Black Hills. When he returns to a family who has been kind to him, “the Big Wind” comes, and when it does, it threatens everything.

The dry, hot wind lashed at the breasts and shoulders of the land. Soon huge dust eddies ran swiftly along the road. Whirlwinds scurried on the paths of the fields and scruffed the bark of the roadside willows. The hot wind moaned in the cracks of the house, sometimes shrilly, sometimes hoarsely, moaning and crying against the house. Towers of dust rose blackly in the night. . .The earth lay gray. The dry wind filled its lungs with dust.

Farm wells coughed and went dry all over the region. Men and women dropped to their knees and prayed for rain. Hucksters showed up with cannons, hoping to pierce clouds that seemed to have forgotten to drop their precious burden. People went cotton-mouthed. Dust-laden lungs killed animals and children, the elderly. There was no water. Most of the parched Great Plains went bone-dry thirsty.

Ironically, that day had begun as a Palm Sunday should—marvelous sun, perfect clarity, the whole northern plains region startlingly clean. But somewhere in North Dakota monster winds picked up and started to blow endless miles of dry soil south, down the Missouri River, into Nebraska and Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas, picking up dust so thick with static electricity that barbed wire glowed and cars wouldn’t start.

The world turned black in a sideways tornado or dirt. People simply resigned themselves to what they believed was the end of the world.

I

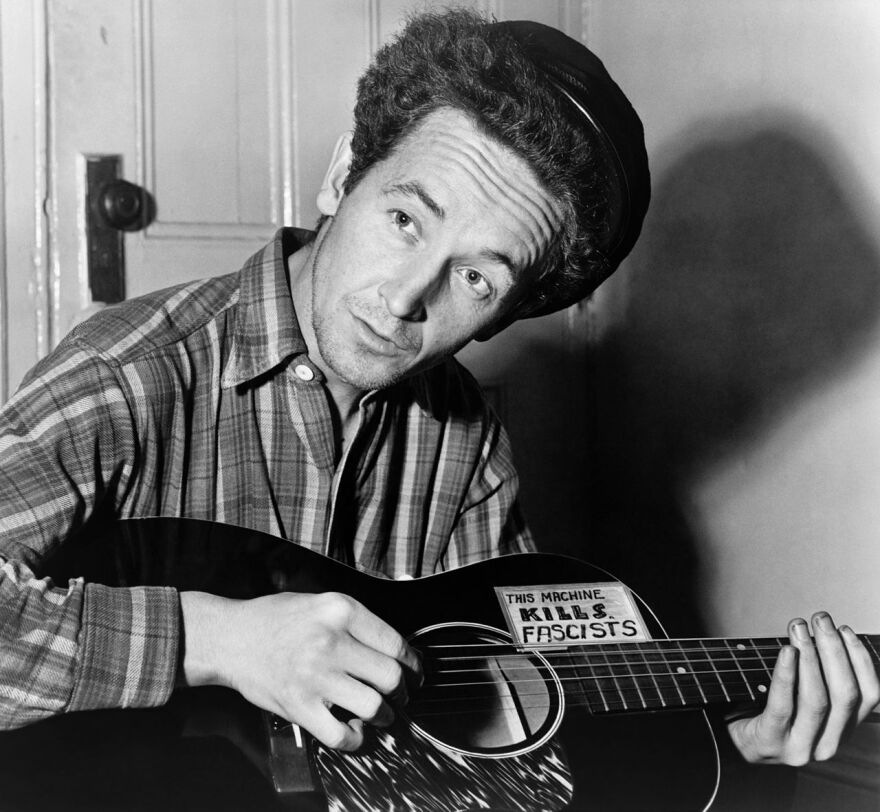

n a town named Pampa, Texas, a gang of people tried to ride out the darkness in the dim light of a single candle between them. One of them had been looking for work, hopping trains, wandering through the desolate land. He’d learned to play guitar while working in a root beer stand that sold whiskey under the counter.

That man said that day, all that dust in the midnight sky appeared to him like the Red Sea caving in on the Israelites.

Right there, with that candle barely lit between them, he started humming. Soon enough he had the first line of a song that, in time, caught on in much of the suffering nation. “So long,” he kept saying to himself, working on a tune. “So long, it’s been good to know you.”

His name was Woody Guthrie.

---

Support for Small Wonders on Siouxland Public Media comes from the Daniels Osborn Law Firm in the Ho Chunk Centre in downtown Sioux City, serving needs of clients in real estate transactions; business formation and guidance; and personal estate planning. More information is available on Facebookor at danielsosborn.com.