Don't remember where I heard it, but the conversation wasn't directed at me. I must have been sitting somewhere among a whole group of people when I overheard a mom telling someone else about her boy, how he was really into his own music, how he was in three or four bands and had already produced his own CDs, how he was going to make music his career, wanted to be a singer/songwriter.

Sure, I thought. He and a half million others. Maybe more.

"That's all he lives for these days," she was saying, or something to that effect. She was proud of him, and I was cynical.

In what seems like a thousand years’ worth of teaching, I saw dozens of young men and women driven to act, to sing, to write music or poetry, to make great films. Hundreds, I bet, and I spent just about all of my teaching life at a small, liberal arts college in Iowa. Imagine how many thousands see similar mirages. Happens so often we make reality shows out of 'em, shows so popular that millions more watch slavishly.

I admit it--I'm being cynical, but I couldn't help shake my head because I've dealt with tons of students who are death-defyingly, soul-deep in similar seductions. You're going to be a singer/songwriter? Sure. Just hang on to your day job, kid.

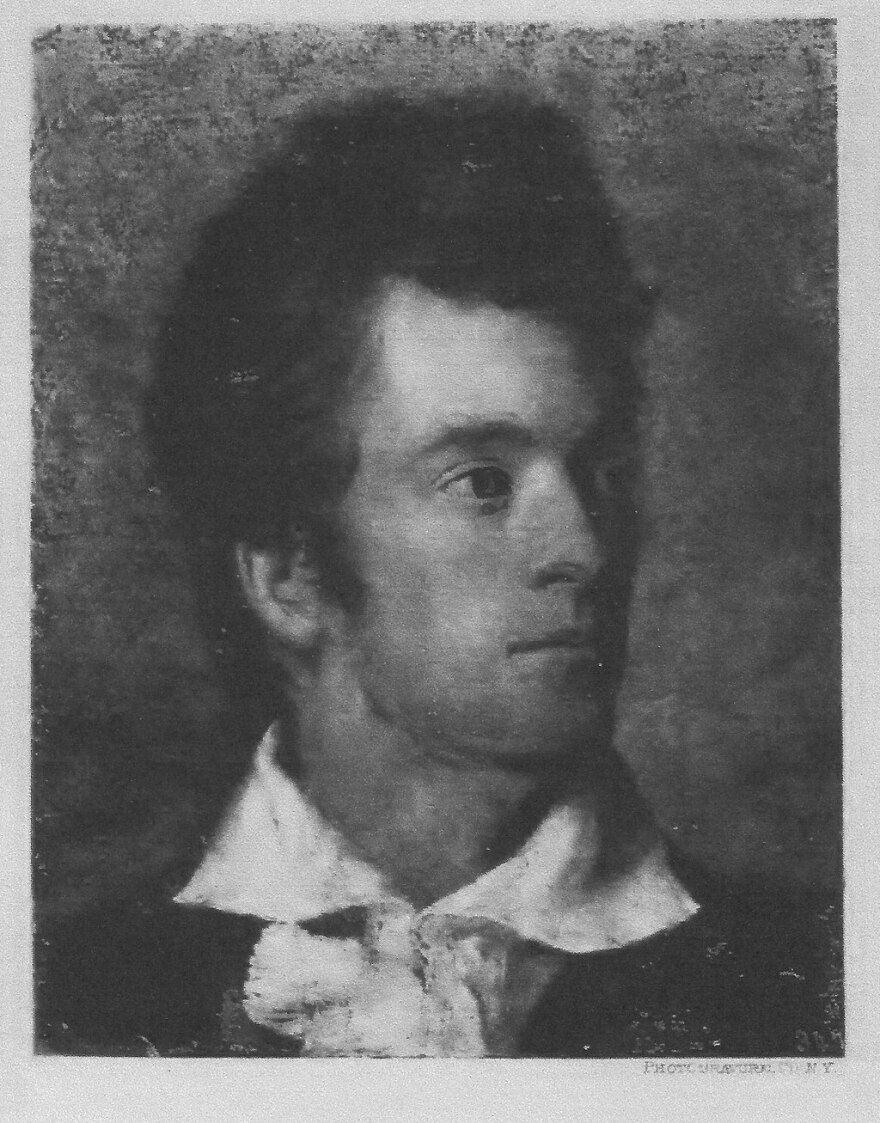

And then, not long ago, for 99 cents, I picked up an old book by a man named George Catlin, just such a dreamer, a lawyer who passed his time in court sketching witnesses, until one day, “Enough,” he told himself, ripped off his lawyer's collar, sold his law books, picked up an easel, loaded up the paints, and, in good American fashion, circa 1830, lit out for the territories. For six years among first nations people and coon-capped fur-trappers, he painted over 300 portraits, landscapes, and still lifes on what white people might still call "the American frontier."

George Catlin followed his dream, and as a result, we've got all kinds of images from a quest that was no mirage at all.

The man was a huckster, a salesman with his own three-ring circus, a Buffalo Bill-grade showman who toured Europe with his American paintings and took with him a gang of Ojibwas who reenacted battles and even scalpings for slack-jawed Parisians. He was Barnum and Bailey with a paintbrush. Mark Twain would have loved him, made him a buffoon if Catlin hadn't done that job on himself.

He doesn't seem to have felt the shame one can feel when pointing cameras at people you don't know. If he did, such shame didn't stop him. I'm sure I'd look at his paintings today--175 years later--differently, if I were Native.

On the other hand, we've got all those portraits. He documented something no one else did, and the paintings are there—go ahead and google ‘em and see for yourself.

He died a pauper, not a showboat, but today his collection sits in the Smithsonian. He followed his dream.

Elders of the Sioux people told him he shouldn't, but way back in 1836 Mr. George Catlin, painting furiously, spent 360 miles on horseback just to find a red-stone quarry in what is today southwest Minnesota, a place where Native folks from all over the continent went to find the soft stone they used for sacred pipes, stone today called "Catlinite." That's right--he came here.

"Man feels the thrilling sensation, the force of illimitable freedom," Catlin wrote about this region of ours. Right there at the monument he carved his name in the rock--I'm serious, he did. "There is poetry," he wrote, "in the very air of this place." You can still read it today.

He's talking about Siouxland, for pity sake--my home. How can you not like him?

Carpe diem.

---

Support for Small Wonders on Siouxland Public Media comes from the Daniels Osborn Law Firm in the Ho Chunk Centre in downtown Sioux City, serving needs of clients in real estate transactions; business formation and guidance; and personal estate planning. More information is available on Facebook or at danielsosborn.com.